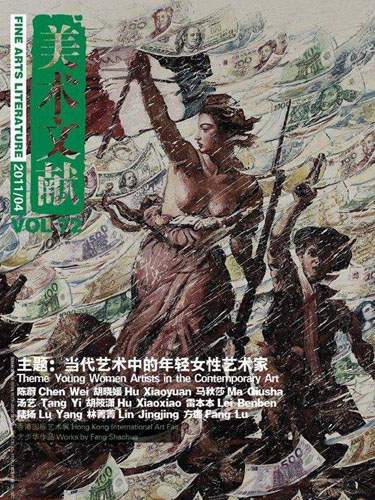

第72期 当代艺术中的年轻女性艺术家(2011年)

学术主持:付晓东 严舒黎

主题:陈蔚 胡晓媛 马秋莎 汤艺 胡筱潇 雷本本 陆扬 林菁菁 方璐

新作:方少华 葛辉 傅中望

Issue No.72(2011)

Theme: No.72 Nine Young Women Artists in the Contemporary Art of China

Academic Host: Fu Xiaodong, Yan Shuli

A.T: Chen Wei, Hu Xiaoyuan, Ma Qiusha, Tang Yi, Hu Xiao Xiao, Lei Benben, Lu Yang, Lin Jingjing, Fang Lu

A.N: Fang Shaohua, Ge Hui, Fu Zhongwang

中国当代艺术中的9位年轻女性艺术家

学术主持:付晓东 严舒黎

在这个关于年轻女性艺术家的主题策划之初,同为女性的我们曾有过非常短暂的怀疑,即当我们将女性艺术家作为一个单独群体讨论她们的作品时,我们其实已经默认了某种“少数性”与“特殊性”。而且不难发现,在中国当代艺术进程中,并非所有的女性艺术家愿意总以这个“女性”群体的身份而被谈及,有些原因是出于反感于社会、媒体对“美女艺术家”的形象塑造,有些是规避被贴上“激进女性主义艺术家”对男权宣战的标签,有些则是对“女性特质”、“女性语言”这些本质论概念的反抗,但实际上,这几种情景提示的正是女性艺术家以及女性主义批评本身在社会中所处的几种尴尬处境。

我们意识到需要非常谨慎地提及女性艺术家这个身份,但只要开始讨论,我们必须承认、正视“女性身份”给这个艺术家群体创作所带来的各方面的现实。而且我们希望这个主题能够引发对这种现实的阐释、讨论与质疑。正如后现代主义所强调的,个体所拥有的“身份”本身即是社会性的,是多元的、流变的、转换的。20世纪80年代,西方后现代女性主义反对之前女性主义对“女性”、“女性特质”等概念的本质论阐释,也反对任何形式的本质主义。与此同时,“社会性别”理论开始出现,这种理论探究性别是如何在各个层面被社会机制所建构,它认为两性并非对立的二元模式,两性平等实际上是一个共同发展的过程。这一理论从“角色、服装装饰、行为等微观层面质疑男性或女性身份存在的必然性与合理性;从公/私的中观层面,挑战传统的社会分工和价值理念;从社会分层制度和社会结构的宏观层面,探讨社会发展与平等之间的关系。”①这些新的理念方法,都让我们最终认为还是可以对中国当代艺术中的“女性艺术家”群体来进行一些有意义的探讨。不过在本期主题中,我们主要关注的是目前活跃于中国当代艺术领域中更为年轻一辈的女性艺术家(生于1970末期—80后初期),希望从这个艺术群体出发,通过关注她们的艺术生存状态、思考线索,比较她们与较早一辈女性艺术家所呈现的相同与差异,当然这些相同与差异,并非绝对的、清晰的,而是穿插的、交融的。

朱其曾在《语言的阁楼——女性前卫艺术的八个案例》一文中对1990年代开始活跃于当代艺术领域的女性艺术家作品描述与概括,他认为:“1990年代中后期,中国当代艺术中的一个令人瞩目的现象是女性主义艺术的真正崛起……女性艺术在1990年代的成熟首先还在于中国女性在中国社会处于急剧变动时期作为女性群体的成熟,尤其是在社会和经济处于巨大变动的大中城市,涌现出一批真正的精英文化女性……1990年代以来中国女性艺术的一个杰出进步,是通过语言进行的一种自我拯救。她们侧重于从自我经历的题材入手,进行形象的自我分析,以及自我语言的虚构。这一代女性艺术家开始真正在艺术语言上有创造力。”②

的确如此,1990年代中后期,随着当代艺术的发展,涌现了一批优秀的女性艺术家,如陈庆庆,林天苗、崔岫闻、喻虹、何成瑶、向京、陈羚羊、姜杰等,这批女性艺术家强调女性生活经验,以女性对自己身体以及曾经拥有的形象的自我剖析为题,她们的作品往往具有以下几个特质:1、关注女性话题;2、质疑女性形象,特别是被父权体制构建的历史、文化所规训的女性“身体”,比如林天苗、何成瑶、向京、陈羚羊、姜杰;3、自觉从自我经历出发,在个人历史与历史文本中寻找被压抑的女性历史,通过女性意识的眼光重新解读男权文化的历史,比如崔岫闻、喻虹、陈庆庆;4、使用与日常女性经验相关的材质,发展一种“女性自我”的艺术语言。比如林天苗、陈庆庆等。这一批女性艺术家实际上与西方1970年代的女性主义艺术家有相似之处,她们“除在图像上寻求符合女性特质的象征外,更以代表女性日常生活经验的材质——布料、编织品,及技法——缝纫、缀补,开拓出崭新的具阴性特质的艺术表现法。”③

但是90年代的中国女性艺术家无疑与1970年代西方女性主义艺术家所处的背景不尽相同。90年代对中国而言,是一个重要的转型时期,对女性主义意识在当代艺术中的自觉而言,也是一个承上启下的年代,它承接了80年代后文革时期对集权主义压抑个性、压抑女性性别特征以及为了所谓的平等而否认男女自然差异的反抗,又开启了自90年代开始的商品经济消费时代以及全球化背景中每个人所面对的多样、复杂的身份问题。而这些新旧问题将在稍后更为年轻的一辈女性艺术家的创作中得以不同的方式转化、解决、搁置或消解。当然,在实际层面上,这些新旧的问题的转化、解决、搁置或消解在部分90年代女性艺术家近几年创作中亦有非常明显的体现(比如尹秀珍、林天苗、崔岫闻等人的新作),只是我们在这一期主题下的这9位年轻女性艺术家作品中能更清晰地得到普遍的论证。

本期介绍的9位女性艺术家,是一般生于70后、80初,并活跃于2000年后的一辈年轻女性艺术家,与生于50、60,活跃于90年代的一辈女性艺术家相比较,这些年轻女性艺术家所面对的环境又有所不同:大多在独生子女的成长环境中长大,使得她们大部分从小与按和男孩一样的期望被养大和受到教育,被要求成为能够独立自由的女性,这一点给她们带来了一种天生在面对两性关系上的平和与自信,当然这种平和与自信只是相对的,她们一方面会感受到自己对父母一辈带给她们的传统价值观念的承继、认同,一方面又会感受到在成长过程中确立的新的价值观念的矛盾、冲突;而随着她们面临的社会形态、价值观念日渐多元,赋予了这一辈年轻女性艺术家可以在多样的身份之间选择、跨越与转换的可能性。(当然同时也可能会带来困惑与不适应);此外,她们与正在快速发展的、更具国际视野的中国当代艺术生态体系一起成长。这一辈的年轻女性艺术家,拥有了较宽阔的国际视野,而对女性艺术家而言更为开放和关注的艺术生态也能够鼓励她们获得一种创作上的自信。当然,更重要的是,这一辈女性的自信、自由度的加强,加大了她们获取更为丰富的社会素材的可能性,信息科技的发展亦为她们提供了多种艺术媒介的可选择性。因此,她们在作品中体现了一些新特点:1、关注的主题较多样,关注女性主题但不执着于女性主题,或较少处于只讨论女性主题的状态。2、在作品中依然重视日常生活体验、关注人际关系,但除了两性体验之外,还常常关注个人/社会之间、人/人之间、人/自然之间,不同阶层、种族、身份之间的关系。3、不回避女性身份,也不特意回避带有“女性特质”的材质和语言,但不在作品中过分强调、打造“女性特质”或“女性语言”,只从构建了她们现实生活和精神世界的观念、情感出发,用适合于主题与自身的材料媒介。4、在她们获得了更多尊重、机遇、宽松的环境的同时,她们也遭遇到变得更为复杂的、隐蔽的、更容易内化为自我冲突的社会性别规训、束缚、偏见与不公正,所以她们的作品依然会呈现出与上辈女性艺术家感受到的同样的矛盾、游离、冲突,但对待这种矛盾的态度,可能不再那么激烈、伤痛,这一辈女性艺术家对自我女性身份所遭遇到的现实,更多的是一种仔细地、慢慢的、平和地认清、辨别与确立,同时也更愿意敞开交流、更不隐瞒困惑与矛盾,尽力在各个层面分析、沟通与建构。正如马秋莎在自述中所说:“自愈内部,然后再用另外的时间来做些别的。”她们在作品中所表现出来对性别的态度,与80年代西方女性主义批评走向第三次浪潮后现代女性主义的主张有着类似的地方,“后现代女性主义理论之主张‘多元性’(plurality)、‘多重性’(multiplicity)、‘差异性’(difference),以及反对不朽的、单一的‘固定形式’之影响。”④

但究竟该如何面对中国变得多元但因而也更为隐蔽的社会性别建构机制?如何面对各种社会意识形态迷宫和复杂的社会现实?如何面对消费社会带来的新的价值、观念的塑造、规训或解构方式?如何面对后殖民主义与西方中心主义带来的中国文化的现实?这些将是新时代给年轻女性艺术家所提出的新问题,当然,这些问题将不再是仅仅对“女性”这个身份所提出的问题,但是“女性”的身份、女性主义的视角,将不可否认会给这些问题带来具有价值的思考方法、角度以及实践。这其实也是集结本主题的另外一个初衷。除了本期介绍的9位女性艺术家之外,还有许多非常优秀的年轻女艺术家,如段建宇、阚萱、曹斐等等,她们的作品也都很明显的体现了上述的几个特点,但出于各种原因,我们没办法在这个主题中一一做出详尽介绍,而且正如前文所言,每位艺术家的个体创作其实也有着非常大的差异,也可以作为一个个案来讨论,更可以脱离“女性”艺术家的身份,而通过其他的身份来讨论她们作品。而且,更为重要的是,我们需要意识到对每个群体的概括和描述都只可能做到相对的、部分的、有选择性的,我们必须在做出任何概括的同时,了解、关注、尊重其他年轻女性艺术家与这9位艺术家不同的承继与探索方向。

在仓促的时间内草成此文,因学养和时间有限,对这一辈年轻女性艺术家创作的概括与分析十分粗略,很多地方都没展开。因而此文只能做为一个话题的抛砖引玉的开始,期待大家更为学理、深入、详尽的研究与讨论。

注释:

①沈奕斐:《被建构的女性——当代社会性别理论》,上海人民出版社,2005年版,P3。

②朱其:《语言的阁楼——女性前卫艺术的八个案例》一文, 2005年。

③、④ 曾晒淑:《女性主义观点与艺术创作、艺术史、艺术评论》(原文:〈女性主义观点的美术史研究〉,载于《人文学报》第十五期,86/6。

Nine Young Women Artists in the Contemporary Art of China

Academic Host: Fu Xiaodong / Yan Shuli

At the beginning of this theme planning on young women artists, we, as women, once had very temporary doubt that when discussing their works by taking the young women artists as a single group, we actually acquiesced in a certain singularity and specialty. And it was not difficult to perceive that in the process of contemporary art in China, not every women artists would like to be talked about with her identity as a member of this “women” group due to the repugnance in the image-building as “beautiful artists” by the society and the media, or to the avoidance of being labeled as “radical feminist artists” to declare war against patriarchy, or to the revolt against the concepts in essentialism like “femininity” and “female language”. But as a matter of fact, the reasons above indicated exactly several embarrassing situations faced by women artists and feminist criticism itself in our society.

We are aware that the identity of women artists must be prudently mentioned, while once there is any need to discuss, we must admit and face the various realities brought to this artistic group by the “female identity”. We hope the theme could initiate the interpretations, discussions and queries. Just as what post-modernism emphasizes, the “identity” possessed by the individual is social, and it is diverse, changing and transformational. In the 1980s, the post-modern feminism in the western world went against the previous interpretation in essentialism about the concepts such as “female” and “femininity”, and essentialism of any kind. Meanwhile, the social gender theory which explored how social mechanism constructed gender in various aspects emerged. According to this theory, both sexes were not in the opposed dual mode, and in fact the gender equality developed mutually. This theory “questions the necessity and rationality of the existence of the male and female identities from the microcosmic view of the role, costume decoration and behavior; it challenges the traditional idea of the division of labor in society as well as value; it probes into the relationship between social development and equality.” ①These new ideas and methods make us finally believe that the group of “women artists” in China’s contemporary art are worth discussing. However, in this theme, we mainly focus on the younger generation of women artists (born between late 1970 to early 1980) in our contemporary artistic field with the hope of comparing them and the early generation of women artists to display their similarities and differences, which of course do not expose as absolute or clear, but interlaced and mingled by paying attention to the condition of survival and thinking clues of these younger generation.

In his “Language Attic—the Eight Individual Cases of Women Avant-garde Art”, Zhu Qi once described and summarized the works of the women artists who were active in the contemporary artistic field from the 1990s. Zhu believed that “in the middle and late 1990s, one of the remarkable phenomena in the contemporary art of China was the real rise of the feminist art…whose maturity lied in the maturity of the Chinese women as the women group when China was in the process that changed quickly. A group of the real elite cultural women emerged in large numbers particularly in the large and middle-sized cities whose society and economy changed enormously…An outstanding progress of the Chinese women art since the 1990s was the salvation by self-help through language. By starting from the theme of personal experience, they analyzed self-image as well as the fabrication of self language. This generation of women artists began to have the real creative power in the artistic language. ” ②

So it is true. In the middle and late 1990s, with the development of contemporary art, a group of excellent women artists such as Chen Qingqing, Lin Tianmiao, Cui Xiuwen, Yu Hong, He Chengyao, Xiang Jing, Chen Lingyang and Jiang Jie emerged. These women artists emphasized the life experiences of women with self-analysis of their own bodies and the images in the past as the theme. Generally speaking, their works had the following characteristics: firstly, they paid attention to female topics; secondly, they (for example, Lin Tianmiao, He Chengyao, Xiang Jing, Chen Lingyang and Jiang Jie) questioned and constructed female images, especially the female “body” disciplined and punished by the history and culture of the patriarchic system; thirdly, they (such as Cui Xiuwen, Yu Hong and Chen Qingqign) felt a compulsion to look for the oppressed female history from personal experience, as well as from the personal and historical texts, and to re-interpret the history of patriarchic culture from the female perspective; fourthly, they (such as Lin Tianmiao and Chen Qingqing) began to make use of the daily material in their experience to develop an artistic language of “feminism”. This group of women artists who “not only went in quest of the symbols in accordance with the femininity, but also explored a brand new feminine artistic expression through the materials—cloth, interweaving, and techniques such as stitching and clouting—which represented the daily life experience of women” ③ actually shared some similarities with the feminist artists in the 1970s of the western world.

However, different from the western women artists in the 1970s, the 1990s for China was undoubtedly an important transitional period, which was also a connecting period between the preceding and the following. It carried on the revolt against totalitarianism that suppressed personality as well as female sexual characteristics and denied the natural differences between men and women for the so-called equality in the 1980s of the late period of the Culture Revolution; meanwhile, it also opened up various complicated identity problems faced by everyone in the commodity economy consumption age under the global background since the 1990s. These new and old problems would be transformed, solved, laid aside and dissolved by the younger generation of women artists in their following artistic creation. Of course, in practical term, the methods mentioned above exposed themselves obviously in the recent creation of the women artists (such as Yin Xiuzhen, Lin Tianmiao and Cui Xiuwen) in the 1990s, and we selected nine of them whose works proved to be more clear and common under our theme.

Active after the year 2000, the nine women artists introduced in this issue were generally born in the late 1970s or the early 1980s. Different from the previous generation of women artists who were born in the 1950s or 1960s, they also faced a different background. Most of them grew up as a single child in their homes, which provided them with the expectation and education the same as that of the boys so as to let them be independent and free. This made them feel calm and confident about the gender relationship. Of course, relative as the calmness and confidence might be, they, on the one hand, felt the acceptance and recognition of the traditional values from their parents, while on the other hand perceived the contradictions and conflicts in the process of developing new values. And as the social formation and values became diverse, possibilities of choosing, stepping over and transforming between various identities were unfolding, which of course would bring confusion and uneasiness. Besides, they grew up with China’s contemporary art ecosystem which developed fast and possessed more international vision. Having a broader international vision, this generation of young women artists were encouraged by this more open and attentive artistic ecosystem to gain confidence in their creation. Certainly, what was more important, the strengthening of confidence and the degree of freedom enlarged the possibility for them to gain richer social materials, and the development of information technology also provided them with choices of various artistic media. Therefore, some new and different characteristics were displayed in their works: first of all, the artistic creation focused on themes of various kinds, in which the female theme was the center but not the only topic, or they rarely talked about this female theme; secondly, the artistic works still paid attention to the daily life experience and interpersonal relationship, but apart from sexual experiences, they also concerned about the relationship between individual and society, individuals, man and nature, and different classes, races and identities; thirdly, their works did not deliberately avoid the identity of women, or feminine materials and languages, but “femininity” and “female language” were not over-emphasized or built. They only chose the materials and media which were suitable to the themes or themselves by constructing the values and emotion in both of their realistic and spiritual worlds; fourthly, when they gained more respect, opportunities and relaxed environment, the more complicated and hidden social gender disciplines, bandages, prejudice and injustice which could easily internalized into self conflicts confronted them, thus their works still presented the same contradiction, drifting away and conflicts felt by the previous generation of women artists. However, the attitude towards these conflicts no longer seemed to be that fierce or painful. Instead of raising their arms in a call for a war or making a complaint about their wounds, this generation of women artists, when facing the reality confronted by their women identity, adopted a careful, slow and calm way to recognize, distinguish and establish. And they were more wiling to discuss openly so as to analyze, communicate and construct in various aspects while no longer hid confusion and conflicts. Just as what Ma Qiusha said in the account of her own life, “to heal the inner side and then to do some other things with extra time.” The attitude towards gender displayed in their works shared some similarities with the view held by the post modern feminism when the western feminism in the 1980s headed for the third tide. “the theory of post modern feminism held the opinion of plurality, multiplicity and difference while opposed enduring and single influence of the stereotypes.” ④

But how on earth could they face the more diverse and hidden social gender construction mechanism in China? How to confront the new values, the shape of concepts, disciplines, punishment or the deconstruction way brought by the consumption society? How to embrace the reality of the Chinese culture brought by post-colonialism and the western centralism? These will be the new problems put forward by the new era to the young women artists. Of course, they were no longer the problems concerning the “female” identity. But it could not be denied that the “female” identity and the feminist perspective would provide more valuable ways of thinking, perspectives and practice, which actually is another original intention of the theme in this issue. Besides the nine women artists this time, there are actually a great deal of very excellent and active young women artists such as Duan Jianyu, Kan Xuan and Cao Fei, whose works also obviously displayed the characteristics illustrated above. But due to various reasons, we can not make a detailed introduction of them in this theme. Just as what the preface says, the individual creation of every artist, which could be discussed as an individual case or through other identities when detached from the identity of “women” artists differ a great deal. More importantly, we need to be aware that the summary and description of every group could only be relative, partial and selective, and when making any summary, we must know, pay attention to and respect the different acceptance and exploration direction between the other young women artists and these nine.

This article was finished within such hasty time due to the limit of learning, cultivation and time. Not fully explored, the summary and analysis of the artistic works of this generation of young women artists seemed to be very rough. Thus, this article, as the beginning of a topic, could only serve as a modest spur to induce more valuable studies and expect others to make more academic, thorough and detailed discussion.

Note:

①Shen Yifei, The constructed Women—Modern Social Gender Theory, Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2005, P3

②Zhu Qi, “Language Attic—the Eight Individual Cases of Women Avant-garde Art”, 2005

③④Zeng Shaishu, “The Feminist Perspective and Artistic Creation, Art History and Artistic Critic” (original text: “The Study of the History of Art about the Feminist Perspective”), Journal of Humanities 15, 86/6